To get to where my mother grew up in Prospect, you would have to go along a dirt road. Best not to do it after dark. Your car might end belly up in a ditch. It is the kind of place where you have to know where you are going or have a local physically show you the way. And you knew when you had arrived by the sound of dogs barking.

My mother’s people are rural. They aren’t speaky-spokey (their phrase for well-spoken), as they don’t have much education, but what they know, they know with a vengeance.

How to kill and cook chicken. The best tea to bring down a fever. Who is mad and why. My relatives have been known to come to blows over the things they know for sure but don’t agree on, and whereas I, as a writer, am struck by the unknowability of things, like how to use a comma properly (the legacy of growing up in a household where stories were oral, not written down). I have inherited their vim for what they know, but also a realization that the more you know, the less certain you can be about things.

I’m proud of my origins. Jamaica has had an outsize influence on the rest of the world, and many of those people came from the very rural areas my parents were from. Bob Marley, Diane Abbott, ME. Despite a lack of privilege, they have succeeded in their endeavours largely because of the courage of their convictions, about the world, about human nature, about their own abilities.

However, there is a tragedy inherent in being so beholden to those things you know, a kind of Stockholm Syndrome to a small basket of ‘facts’ that hold the sky up.

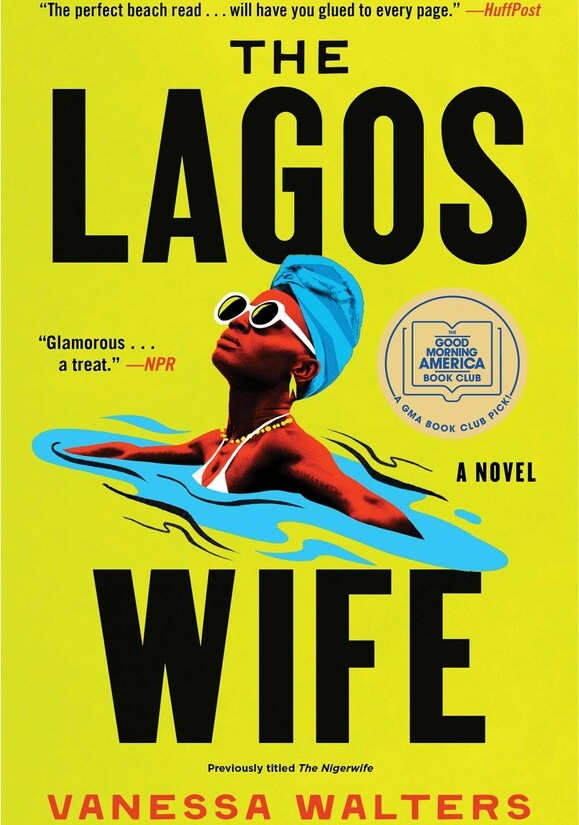

In my novel, The Lagos Wife, the Roberts family from South London, like my elders from Prospect, Clarendon, are very clear on what they know they know about Nigeria based on a single television programme they watched called ‘Welcome to Lagos’, a documentary set on a rubbish dump. Only Claudine questions it. She travels to Nigeria to find out what has happened to her missing niece, but her journey is also one of questioning these fiercely known things of her family.

Remember when former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was trying to explain away the fake reasons to go to war in Iraq, he said that there were the known knowns; the things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns; the ones we don’t know we don’t know (Yeah, the worst person gave us possibly the best word salad of the modern age).

Claudine realizes she has been held hostage to just a few known things her entire life. They all have. Those things became an emotional straitjacket. Who you could be, what you could do, and why all become subject to those known things.

The more she finds out about Nicole, along the way being exposed to the very different culture of Nigeria, the more she realizes that some of those known things are not set in stone, that she is free to take a different path, to be a different person. It isn’t too late.

She goes beyond the horizon of the things she has always known and realizes just how much those known things hold us together, but the opportunity of not knowing too. The things we know can also be a straitjacket.

On the page, your worldview, your deeply held opinions, those things you are in conversation with yourself about all the time, will be represented in your writing style, your choice of words, of characters, of settings. Your convictions are your ‘voice’. Wither they come from high or low places, be proud of them, but don’t let them be a straitjacket. Interrogate them as you go along. Leave a space for unknown unknowns.

I just finished reading The Coin by Yasmin Zaher.

The book is the grippingly sad, funny, and disturbing story of a Palestinian teacher going through it in New York City. If you’re a fan of My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh or Luster by Raven Leilani, you will love this. She has a few plot points that go nowhere, but the book is riveting nonetheless and very deserving of the Dylan Thomas First Novel Prize. At times, it seems that the author, like her main character, is a little lost and doesn’t quite know where she is going. We don’t even learn her name. It feels painful, but it also feels like a necessary exploration of painful things, both for the reader and the writer. You must have the courage of your convictions to even be a writer in the first place, but leaving a space for the unknown unknowns is perhaps the most courageous thing a writer can do.

Love this passage: “…there is a tragedy inherent in being so beholden to those things you know, a kind of Stockholm Syndrome to a small basket of ‘facts’ that hold the sky up.”